There may be no more important debate in AI policy right now than how power to regulate AI should be divided between the federal and state governments.

We first wrote about the respective roles of Congress and state governments in early 2025, as we saw states throughout the country introducing bills that would regulate how AI models are built. A patchwork of state laws poses a threat to Little Tech: small companies are at a competitive disadvantage with larger platforms when states like Texas, California, Florida, and New York impose different, and potentially conflicting, legal requirements. Startups don’t have the deep pockets and large legal teams that their competitors have, so they suffer when they are forced to navigate this type of regulatory landscape.

As we wrote then, there is an important role for both states and the federal government in governing AI. The starting point should be that Congress and state governments each play the role the Constitution assigns to them, with the federal government leading the regulation of interstate commerce and states policing harmful conduct within their borders.

These core constitutional principles have not historically broken down on party lines. While current AI preemption proposals have been primarily advanced by Republicans, bipartisan coalitions have introduced similar concepts in the past, and the Biden administration’s Justice Department raised concerns about the extraterritorial effects and out-of-state burdens of California laws. It emphasized that “[t]he combined effect of those regulations [on pork production] would be to effectively force the industry to ‘conform’ to whatever State (with market power) is the greatest outlier.”

Now, with speculation about potential Congressional action to clarify the role of the federal government in regulating AI, the same questions proliferate: What can Congress regulate? What can states regulate? And where are the constitutional limits on their respective governing powers?

We asked a panel of leading appellate lawyers to explain the state of the law on these questions.

Allon Kedem, partner, Appellate and Supreme Court practice, Arnold & Porter, Paul Mezzina, partner, Appellate, Constitutional and Administrative Law practice, King & Spalding, and William Jay, partner, Appellate and Supreme Court Litigation practice, Goodwin, join Matt Perault, head of AI policy, a16z, to explain how federal preemption, the dormant Commerce Clause, and the First Amendment intersect with AI policy in this moment.

This is part one, focused on preemption. Stay tuned for upcoming conversations on the Commerce Clause and the First Amendment.

This transcript has been edited lightly for readability.

Matt Perault (00:00)

So I think there probably is no debate in AI policy that’s more important right now than what the role is that states should play in AI governance and what the role is of the federal government. We saw this play out in a really brilliant bright way over the summer with the debates around the AI moratorium, where Congress introduced a proposal to preempt some aspects of state policy. And there were lots of questions about what was lawful and what wasn’t.

So what is Congress permitted to do and where are the bounds on congressional action? What are states permitted to do and what are the bounds on state action? So we thought it would be really helpful to gather a panel of esteemed lawyers to provide us with some guidance on those questions and understand more deeply what the legal bounds are for how we think about AI governance. So maybe we can kick it off, Allon starting with you and talk a little bit about preemption just to understand exactly what the term means and then what are the legal guardrails around what is permissible for Congress to do when it’s attempting to preempt state authority.

Allon Kedem (01:02)

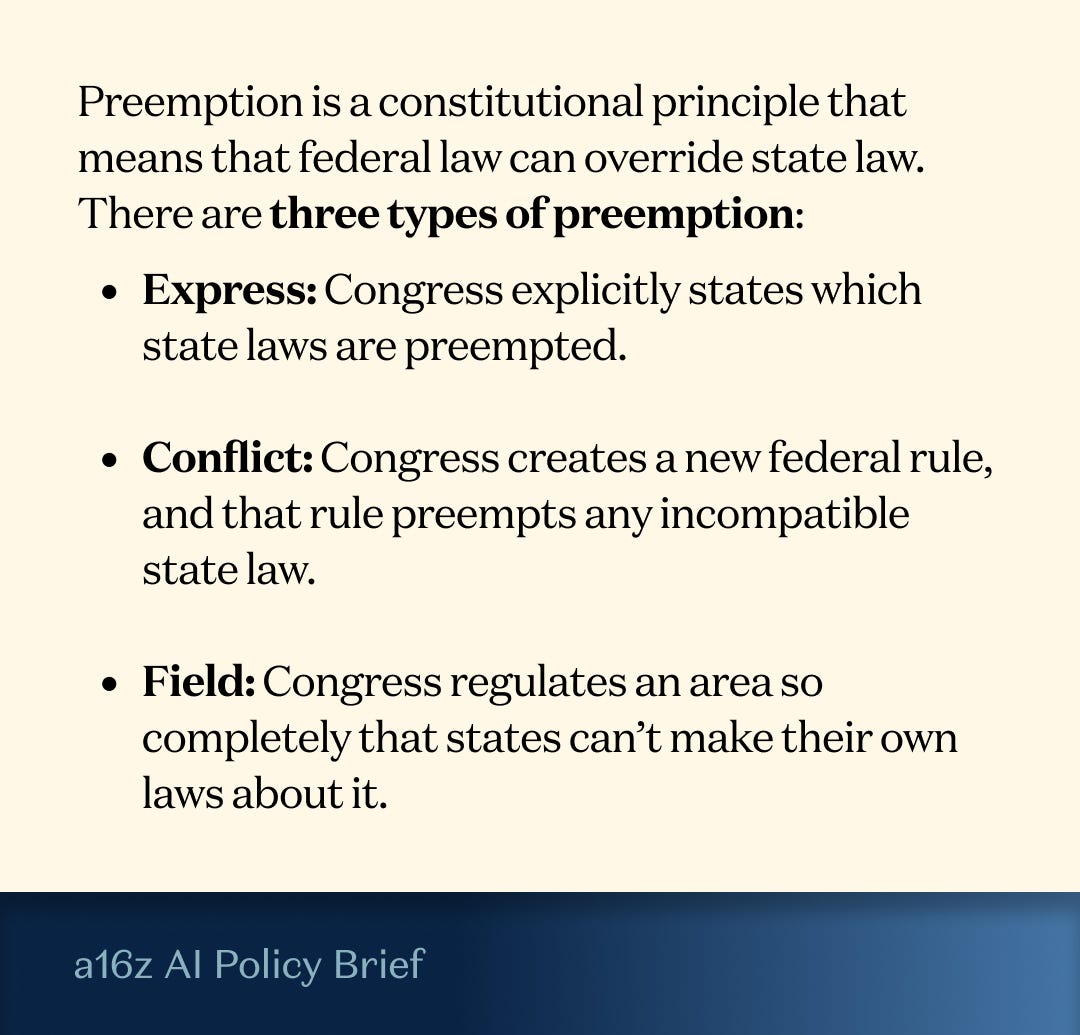

Sure. So preemption is a legal principle that flows as a consequence of the Constitution Supremacy Clause, which says that the Constitution and laws made under it, in other words, federal laws, are supreme, notwithstanding anything under state law. And that means that when there’s a conflict between federal law and state law, federal law needs to prevail. And there can be several different types of conflicts and thus different types of preemption.

One, pretty straightforward one is express preemption where Congress says that states are prohibited from enacting certain types of laws or they say that federal law predominates over state law in a particular area. There’s also a form of preemption called conflict preemption where sometimes it’s impossible for federal law and state law to be complied with at the same time in which case federal law again prevails. That could be an instance where, for instance, federal law tells you, tells a regulated party to do something and state law says that they shouldn’t do it or vice versa. There can also be a conflict even at a sort of higher level of generality where federal law embodies certain policies or values that state law directly conflicts with and undermines.

And then the final area is something called field preemption, which is usually where there is some subject that is regulated by the federal government in such a complete and pervasive way that it just leaves no room for states to enact statutes in the same area, even if the state statutes aren’t directly in conflict with federal law. So any one of those could lead to a finding of preemption, in which case federal law would prevail over state law.

Matt Perault (02:42)

One thing that would be really helpful for you to clarify is whether it’s necessary for Congress to take action in a specific area in order to preempt an equivalent area in state policy. So we hear all the time things like in order to preempt state laws on transparency or state laws on liability or state laws on national security issues related to AI, Congress needs to take action in the equivalent area. So you need congressional action and transparency in order to preempt state activity and transparency. Is that the case?

Allon Kedem (03:13)

Not necessarily. So you do need some affirmative source of federal law for there to be a conflict with state law, but it doesn’t have to match the state law precisely. So it doesn’t have to be the case, for instance, that there’s a federal transparency law and therefore states can’t enact laws in the same area of transparency. It could be a federal law dealing with, you know, one subject in a very general way that has sort of knock on effects for state law. And so an example of that could be something like know, Section 230, which was a law that Congress passed sort of at the dawn of the mass internet age that had all sorts of preemptive effects on state tort law, for instance, or in some instances on state contract law, even though Section 230 itself is not a tort law or a contract law.

Matt Perault (04:00)

I think some people have in their heads the idea that like, if Congress is going to act in preemption, we need to see this like a federal AI framework. We need to see a law that’s something AI related, has lots of provisions related to lots of different AI related issues. It sounds like what you’re suggesting is like that’s one vehicle, but wouldn’t be the only way, at least legally to accomplish preemption if that’s what Congress was trying.

Allon Kedem (04:25)

That’s correct. Although, you know, one feature of preemption is that because there is a sort of default presumption that states are independent sovereigns who get to enact their own laws, it is usually advisable if Congress does want to preempt state law for them to be a little bit explicit about it, or at least to sort of make their wishes in the area known with sufficient clarity, because otherwise you run the risk that whatever they have in mind is not going to get carried out.

Matt Perault (04:55)

So Willy, that’s a good opportunity to segue to you. Could you talk a little bit about where the limits of federal authority would be? If Congress decides that it wants to preempt some state activity, is it able to do that however it wants or are there some limits to its authority to enact something that preempts?

William Jay (05:15)

The main limits come from the Constitution and they can come from basically three things. One is the extent of Congress’s power to regulate. So for example, Congress has granted power to regulate interstate commerce, but there are some things that historically the Supreme Court has considered to be too local and too non-commercial to fall within a commerce power.

Some are things that have to do with states themselves as sovereigns under the sovereignty that states retain under the 10th Amendment. And some have to do with the individual liberty that the Bill of Rights and other provisions of the Constitution guarantees. So obviously Congress can’t create a federal regulatory scheme that violates one of the protections of the First Amendment or the Fifth Amendment, for example. But for a long time, Congress’s power seemed to be basically unlimited, except where it stepped on one of those individual guarantees.

In the mid-1990s, the Supreme Court started putting more teeth back into the limits of Congress’s power under the enumerated powers doctrine, the idea that our national government has only the powers that the Constitution grants it and no more. But still in the technology space, almost everything intersects with commerce, the channels of commerce, the way that people do business. The commerce power is still very, very broad, even if there have been a handful of guardrails put around the commerce power.

Matt Perault (06:57)

So how do, can you talk a little bit about how those principles might map on to something specific that we would see in AI? So like you could use the moratorium from the summer as one example, but that doesn’t have to be the only one. Like what are the kinds of things that federal lawmakers should consider when they’re thinking about, is this legislation going to run into 10th Amendment concerns?

William Jay (07:16)

Well, one thing that Congress often does is it puts something jurisdictionally connected into its regulatory statutes. even things that don’t sound like commerce, like should there be guns near schools, Congress can put something into a statute that says in or around a program that is funded with federal dollars or things like that.

So in the context of the moratorium, for example, might think about what are the areas that are traditionally the states to regulate that a blanket moratorium might step on and that might wind up being a subject of challenge. So for example, states usually regulate the practice of medicine. And so I could see some argument that a very broad but non-specific federal law shouldn’t reach the actual sort of standards for medical malpractice, including whether doctors should or should not use AI for diagnosis.

Matt Perault (08:16)

And what about commandeering principles? Like if you’re saying no state shall, is that essentially a dictate? Like the Congress dictating to state lawmakers that they’re not able to act.

William Jay (08:27)

So there’s a difference between sort of the positive and the negative. So in other words, Congress can stop states from doing things that violate federal law. Federal law is supreme, state law is subordinate in that sense. But what Congress can’t do is enlist the states basically as it’s sort of cat’s paws.

So you can’t say in a federal law, the states shall pass their own laws that do X. So you can say, no state laws that look like X, but you can’t say the states shall pass laws that do X, nor can you enlist state officials, which could include everything from, know, sheriffs to boards of education, to boards of regents, in doing the hard work of enforcing federal regulation if they don’t want to be.

And this has come up in the immigration context quite a bit recently, where states and localities have said, our cops will not enforce federal immigration law. The federal government doesn’t like that. And there have been, there’s been pushback about that.

But, the basic principle is what you alluded to, Matt, the idea that you can’t, federal government can’t commandeer the states into doing the national government’s work. It has to do that itself.

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Furthermore, this content is not investment advice, nor is it intended for use by any investors or prospective investors in any a16z funds. This newsletter may link to other websites or contain other information obtained from third-party sources - a16z has not independently verified nor makes any representations about the current or enduring accuracy of such information. If this content includes third-party advertisements, a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content or related companies contained therein. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z; visit https://a16z.com/investment-list/ for a full list of investments. Other important information can be found at a16z.com/disclosures. You’re receiving this newsletter since you opted in earlier; if you would like to opt out of future newsletters you may unsubscribe immediately.